A glyphosate-based herbicide cross-selects for antibiotic resistance genes in bacterioplankton communities

Naíla Barbosa Da Costa, Marie-Pier Hébert, Vincent Fugère, Yves Terrat, Gregor F. Fussman, Andrew Gonzalez et Jesse Shapiro

|

Naíla est une écologiste qui a quitté sa terre natale du Brésil pour poursuivre un doctorat à l’Université de Montréal afin de mieux comprendre comment les microorganismes des milieux aquatiques font face à la contamination des eaux par les pesticides couramment utilisés en agriculture. C’est dans l’ADN des bactéries qu’elle trouve les réponses à ses questions.

|

FR: Naíla qui travaille ses séquences génomiques de bactéries planctonniques issues de ses expérimentations d'étangs. EN : Naíla working with genomic sequences of planktonic bacteria found in the experimental ponds © Johnnatan Nascimento

FR: Naíla qui travaille ses séquences génomiques de bactéries planctonniques issues de ses expérimentations d'étangs. EN : Naíla working with genomic sequences of planktonic bacteria found in the experimental ponds © Johnnatan Nascimento

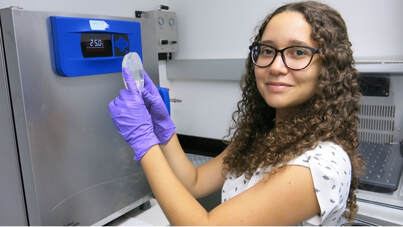

Naíla Barbosa da Costa holding an agar plate containing bacteria isolated from experimental freshwater ponds © Johnnatan Nascimento

Naíla Barbosa da Costa holding an agar plate containing bacteria isolated from experimental freshwater ponds © Johnnatan Nascimento